The making of Clouds of Perseus – Part I

November 2011

Clouds of Perseus is a collaborative project between Bob C., Eric Zbinden, Al Howard, and myself. This article describes how this project came to be, from beginning to end.

Part I mainly talks about the planning and data acquisition.

Part II will talk about the post-processing of the data into the final image.

Part III will talk about the making and testing of the light box.

The idea

Early in the summer of 2011, Bob Caton approached Eric and I and told us this idea he had to build a huge lightbox to display at the following AIC (Advanced Imaging Conference), displaying some astrophoto. Of course, the idea was to capture the image by ourselves.

Eric and I agreed to work on capturing the data (Al would join later). Of course, we also had to decide what to photograph. Originally Bob had the idea to do a large mosaic in the Cygnus area. I hesitated alleging that the Cygnus area had been photographed plenty of times, and although it would certainly look amazing in the lightbox, we should try to go for something less “ordinary”.

I suggested something in the region of Perseus and Taurus that would include the California nebula, or the Pleiades, or both. This suggestion came from knowing well this area is crowded with interstellar dust. Eric immediately agreed and so did Bob.

Timing is everything

We had one problem, and not a small one. In order to have the light box ready for the AIC, we only had until September’s New Moon period to finish capturing the data, as the printing of the negative had to be done by mid-October.

It takes a quick look at any planetarium software to see that this area of the sky is impossible to photograph early in the summer, and if we were to use the months of August and September, we would have to wait until at least 1-2am in August to start imaging, and not much earlier than that in September. This limited our imaging time considerably, to the point the idea was almost rejected thinking that we might just not have enough imaging time.

It is worth mentioning at this point that neither Al, Eric or I have permanent or remote observatories, and all the data would have to be captured “in the field”, that is, driving to dark sites every night we had to capture the data. Also, because we wanted to go deep, moderately dark skies were not sufficient – more on that later.

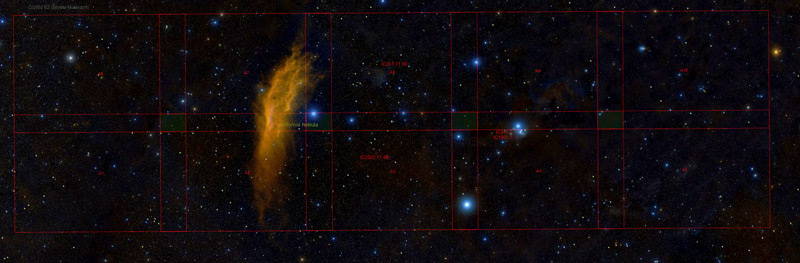

The framing

Because the light box was going to have very specific dimensions, we had to define our mosaic according to the proportions of the light box. Although the idea of an image including the California nebula and M45 was very appealing (I would know, as I captured this area back in 2009), this constraint with the proportions forced us to choose one or the other, and then try to define a field of view that would “make sense”. We settled for the California nebula, and defined the FOV towards IC 348 and NGC 1333. It took a few tries… We first agreed we didn’t want NGC 1499 too much to the left of the image, and with that in mind, Bob presented a framing very well balanced, I made a small adjustment, and we agreed to go with it. Bob punched in the coordinates so we all would get the very same numbers, and we finally were in agreement. Although Eric and Al were going to use a FLI PL 16803 camera, we agreed to define the mosaic using the FOV of the 11000 CCD – basically, using the smaller FOV that was going to be used.

Planning

We agreed that Bob would capture H-alpha data from his observatory in Modesto, for the area of the California nebula, and then, Eric, Al and I would go for the LRGB data. I pointed out that the best way would be if each of us were assigned certain panes, and then did the complete LRGB for those panes – as opposed to, say, have Eric capture the red data, Al the green and me the blue.

As the New Moon period for August was approaching, and since nobody else was “making the decision”, I quickly assigned panes this way:

Bob: Panes 2 and 7, H-Alpha only

Eric: Panes 5, 9, 10 (LRGB)

Al: Panes 3, 4, 8 (LRGB)

Rogelio: Panes 1, 2, 7 (LRGB)

This selection wasn’t completely random. Eric and Al’s areas were for the most part, adjacent, which made sense since they were going to use the same type of camera. And the area of the California nebula was assigned to the STL 11000 (me), since it is a high signal area compared to the more dusty areas. Yes, pane 1 (also assigned to me) only contains extremely faint dust, but in order to meet the other conditions, it was either pane 1 or 6 for me.

If you notice, yes, pane 6 is missing in the list above. With three panes per person (fair and square), what I suggested was that whomever finished his three panes first, would go for pane #6. By the way, ultimately it would be Eric the one who captured pane number 6.

We also agreed on capturing a minimum of 4 hours of luminance per pane, as well as 2 hours per color channel, all bin 1×1 of course, and with 15 minutes subs.

When doing the numbers, counting the nights, considering the target wasn’t well positioned in the sky until late at night, etc. we knew that the weather had to cooperate 100% every single “New Moon night” we could go out to image, or we would just not make it. Stressful? Just a bit 🙂

Capturing the data

Al, Eric and I started collecting data on August 27th, 2011, at the DARC Observatory, while Bob also started capturing H-Alpha data at his home-based observatory in Modesto.

Eric and Al used a very similar setup, with AP900 mounts, Takahashi FSQ106 scopes and the FLI Proline 16803 camera. I used a Takahashi EM400, another Takahashi FSQ106 scope, and the SBIG STL11000 camera. Bob also used a SBIG STL11000 camera, and yet another Takahashi FSQ106 telescope, all on a Paramount ME mount. The fact we all were using the same type of scope and that all cameras had the same pixel size, made everything a bit easier, as no resampling would be needed during mosaic assembly or post-processing.

A few words about the DARC Observatory. It is actually property of Bob, sitting in the blue zone (Bortle scale), and it’s about 120 miles away from where Eric and I live, and about 110 miles from Al’s home.

This means that every time we would go to DARC to capture data, we would have to drive 120 miles to the site, usually fighting the evening rush hour traffic, and then 120 miles back, in the wee hours of the night – most of the times fighting the morning rush hour traffic! That’s not just 240 miles for every single single session, but 240 miles that includes dealing with rather heavy traffic conditions for about half of the trip. An of course, taking everything out of the car and setting everything up at the beginning of the session, and tearing down and packing it back to the car at the end, every… single… night.

Here’s an image of the three scopes, set up in the open dome at DARC, capturing data for the project:

Left to right: Eric’s, Al’s and my scope. The distortion you see in the image is due to a 10mm lens being used to take this photo. If you pay attention you might even see Eric’s “ghost” sitting at his table 🙂

I believe Eric imaged almost 14 days in a row (!!!). I know I did 8 days in a period of 14 days, and although I don’t remember Al’s schedule, it was just a tad shorter than mine. Some simple math then tells us that if you were to add the miles driven by Eric, Al and I during these14 days of New Moon period to the DARC Observatory, we’d be talking about approximately 7,000 miles and over 110 hours at the wheel. I’ve lost track of the time spent at the site, but the numbers are probably just as crazy. The fun part? We were not even nearly done, and another Herculean… I mean Perseulean effort coming up for the next New Moon.

Besides everything I’ve mentioned, driving 2 hours to a dark site during weekdays is also not easy business, as we all have to, well, WORK the next day, so although neither of us were using automated software to program our sessions, whenever we had a chance, we would set up a cot inside the observatory and try to catch a few zzz’s… just not too many, and certainly, never more than a few in a row… here’s my cot waiting for me:

By the way, don’t be fooled 🙂 Although the image is all bright and the room looks nice and lively, during our imaging sessions we keep the building with minimum red lights only, so the atmosphere in the room is always rather gloomy when we’re there doing our thing. Don’t get me wrong, I love DARC, I just don’t want you to get the impression that during our imaging sessions we enjoy “normal” lighting and activities 🙂

More data!

The new moon during late August and early September wasn’t nearly enough to complete the mosaic. We needed great weather during the next New Moon, and so we waited patiently for it. And when it came, although the forecast for the first few days wasn’t so great, Mother Nature gave us a break, just long enough.

This time around, Al and Eric continued going to DARC, but I actually headed to the Central Nevada Star Party (CNSP), seeking some of the darkest skies in the country. A rather moody weather didn’t give me those greatest skies the CNSP is famous for, but I was able to finish my part under fairly good skies after all – just not nearly as dark as the site for the CNSP could get. Al and Eric also managed to finish their part, not without some sacrifice as in “I wish I were done, I could use some rest, but I need to go again tomorrow” perhaps a couple of times.

Take away one night and we would have not been able to finish. It was THAT close!

But the weather cooperated and gave us all the nights we needed, and finally, after another intense New Moon period, we were … done!!

Of course, I had this little incident I wrote about the other day, but the outcome from that night was good, and so we finally had all the data we wanted.

With all the data, what was left for us to do was to calibrate our subs, generate our own master L, R, G and B – and H-Alpha for Bob – and share the masters with the team.

There was not one particular person assigned to do the processing. The idea was basically to share the data and whomever wanted to have a go, just do it. In the end, only Eric and I decided to go for it, and he ended up having to concede the work to me, as he got extremely busy at work and with not enough time to do his processing on time. In the next part of this article I will talk about how I processed the data, from mosaic construction to final presentation, and everything in between.