The Value of an Astrophoto

September 2011

Can an astrophoto represent reality of what is out there? Can an aesthetically-driven astroimage have scientific interest? Can we talk about science versus art, when comparing astroimages that have been minimally processed with images that have gone through some more complex post-processing? Do minimally processed astroimages have more value than those with a more involved post-processing?

These being recurring topics in the astroimaging community, I’ve decided to post my thoughts here – it will make it easier next time someone brings these issues, once again, somewhere…. 🙂

(I use the terms “minimally processed” and similar throughout this article referring to images that may only include during post-processing a small set of operations such as deconvolution, DDP, some non-linear histogram transform and little more. It is not meant to be a derogatory term in any way.)

And here’s what I think…

Can an astrophoto represent reality of what is out there?

I believe that in astrophotography there’s no such thing as a natural or realistic appearance. Reality in an image is just impossible to depict, and even more so in astrophotography. The reasons why I strongly believe this might take some writing, and there are other points I’d like to cover without you falling asleep before you get to them, so I’ll probably go back to this topic at a future date. For now, just think for a second: we’re trying to represent objects and structures that are thousands or millions of light years away and that are often larger in size than what our mind can even conceive… and we’re doing that right in front of our eyes, and in a monitor that at most is just a few inches wide (not to mention the extremely poor dynamic range they can represent). How’s that for real?

Can an aesthetically-driven astroimage have scientific interest?

Actually, I don’t think scientific interest is something that needs to pass the “is it minimally post-processed?” test.

The way I see it, there will be aesthetics-driven images that might ignite some scientific interest, and likewise, there will be images minimally processed that may never attract the interest of scientists at all. It’s quite simple. For example, when some astronomers saw this image I took of the Virgo galaxy cluster, (overprocessed to some, of course) they contacted me to provide them with a non-linear stretch of the raw data – which I did, and it proved to be quite interesting (I cannot say more than that at this time, sorry). Should I have not pushed post-processing with some techniques such as HDRWT, wavelets, morphological transformations, etc. the image likely wouldn’t have ignited any “scientific interest” at all.

Yes, if your post-processing has introduced artifacts that haven’t been seen before, you might ignite some scientific interest for the wrong reasons, and that’s why you must be careful not to introduce such artifacts! But other than that, this debate is quite simple, there shouldn’t be a debate.

Can we talk about science versus art, when comparing astroimages that have been minimally processed with images that have gone through some more complex post-processing?

This is another topic that I don’t quite know why it’s brough out so often. It’s as if there’s some sort of consensus that astrophotography needs to be separated into the “science approved” images and “astro art” or something, when the way I see it, that’s a neither and nor…

I don’t usually consider an astrophoto to be pure “science” once the image is no longer linear, so, unless the post-processing involved incurred in blatant inventions, I don’t usually make the distinction of “science vs art” with images that are non-linear when presented to the viewer, regardless of the amount of post-processing.

So when these topics come up at mailing lists, web forums or even conversations, I don’t think it’s correct to talk about “science vs art” as if those folks who do minimal processing to their images are producing science-approved images while everyone else is doing just “astro art“.

Of course, some of these folks will tell you otherwise, but the way I see it, in most cases, both groups are producing something that has inherited qualities from combining both disciplines – art and science. And that is what astrophotography really is, as far as I’m concerned. In simple terms, if it’s only science, you’re doing astronomy, and if it’s about aesthetics and nothing else, it’s likely just art. To me, astrophotography is a bit of both – yet not a whole lot of either – and if one of them is missing, then it’s something else.

Are we not respecting the data when we apply post-processing techniques such as the star reduction method described here? Are we being unethical?

I disagree that techniques such as the “star reduction” method (link above) and many others show no respect for the data (more on that later) or are unethical, but regardless of what you think, to me, bringing up that question is, once again, missing the point completely about what the value of astrophotography is. In the next paragraph you’ll probably understand – agreeing or not – what I mean by that.

Do minimally processed astroimages have more value than those with a more involved post-processing?

What I believe is that an image can have documentary value, whether the pixels around a star have been dimmed, have inherited values from the surrounding pixels, or have been left intact after some operator-chosen non-linear histogram stretch. And such documentary value can be just as valid regardless of which of the previous operations have been performed.

What matters is the intent of the operator and there’s a lot one can say about that. Of course, one can start “inventing features” to the point the image may lose its documentary value. This is not to say that doing such things are necessarily “wrong”, because astrophotography can also have a worthwhile emotional and aesthetic value despite some people who say are science-driven may ridicule the idea… When you go that far, it simply means that the image no longer has documentary value, and it should be treated, viewed and analyzed as such.

As I said earlier, to me, generally speaking, if you like to analyze data, you should stay in linear-land, and once you cross that line, your image enters the documentary zone. This is an area where your image is subject to certain personal treatment and interpretation. Whether you are content by doing a couple of post-processing operations such as deconvolution, a non-linear stretch, and a few more, or take advantage of many other post-processing techniques that can indeed enhance the documentary value of your data, that’s a personal choice.

And within that personal choice, in some cases, and depending on the goals, a minimalist processing may in fact be a very good choice for bringing up some very good documentary value in an astroimage (some people in fact favor the look of such images, but we’re not talking about the look of astroimages here, so comments in that regard aren’t needed in this discussion).

What I believe however is that by limiting yourself during post-processing to a restricted set of techniques “because I want to respect the data”, laudable as it might be, you might also be missing an opportunity to increase the documentary value of your image, while still respecting your data. And here’s the thing… As long as you are increasing the value of your image, you are respecting the data, simply because you’re utilizing the data to present an image that not only holds value above purely aesthetics, but it also maximizes what is really worth. It is only when you depart from that documentary value when your respect for the data decreases.

So, if maximizing the possibilities of your data with the purpose of increasing the documentary value of your image is – according to some people – a “disrespect” for your data, what exactly is to NOT maximize it and produce an image with a likely less documentary value?

Of course, some people may not buy this explanation about “documentary value” or may view it differently. If they did, I wouldn’t have a reason to write this, now would I? 🙂

In any case, if you want your image to possibly miss on that increased documentary value because of the way you value your data or because of your beliefs of what is ethical or not, that’s fine. As I said, that can be a valid option. However I have no desire to show complacency to any statement that regards astrophotography as a discipline that should limit itself to a couple of simple techniques during post-processing in order to have value or to be considered ethical, because, as stated, IMHO, where those who think that way believe the value ends, some of us take on and keep on adding the value they ignore, disregard or are simply shortsighted enough to not recognize it.

From this point of view, I don’t think minimally processed astroimages have more value than those with a more involved post-processing – to me, often times it’s quite the opposite, in fact. And this is without getting into the topic of aesthetic value, because that’s another deal, not to be disregarded.

An image is worth a thousand words

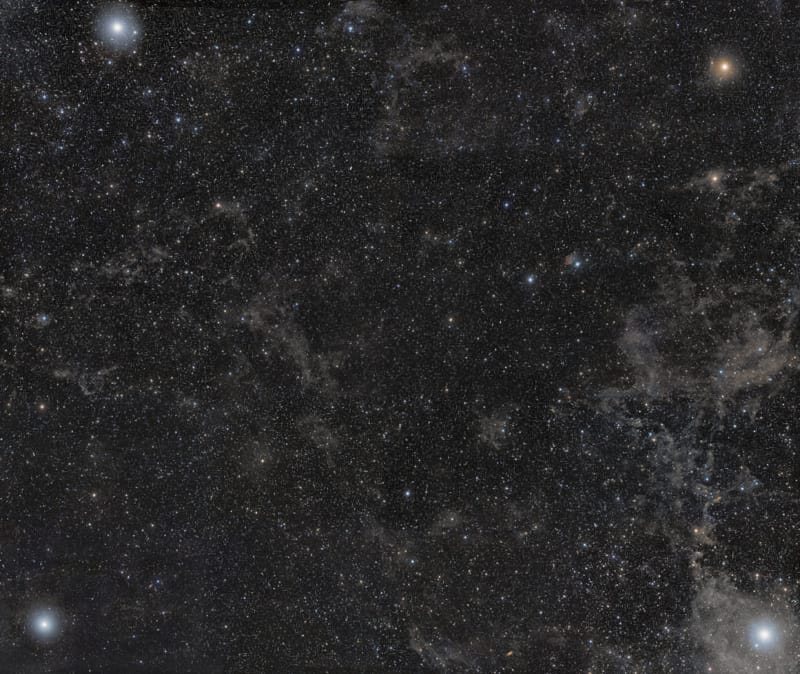

Recently I took an image of the Great Square of Pegasus, a 20 panes mosaic. After all the work of putting the mosaic together seamlessly, my first post-processing steps were basic non-linear histogram adjustments. Right before I started to utilize more advanced techniques, the image looked pretty much like this:

That is the equivalent of what some would describe as “minimalistic processing”. And I could have stopped there. And that image has some undeniable value. But a strong (linear or not) inverted stretch revealed a lot of faint structures, and I wanted to visually document those structures. Not measure, not analyze, simply trying to produce an image that would be able to show the shape, position and relative surface brightness of those structures, hopefully without destroying the appeal of this starry area of the sky. For that task I knew I had an arsenal of techniques – not tricks – that could aid me in reaching that goal (and for those interested, no, such techniques don’t involve the use of the brush, lasso or similar tools). So there was my choice. Should I stop here and present an image of lots of stars, or go further in the post-processing? Well, to me it wasn’t even a choice. I knew I wasn’t going to stop there… A reduced version of the final image is here:

Now, when you end up with an image like the one above, you have to expect that some people is going to say – or think – that the image has been overprocessed, perhaps even say things like “those clouds of dust look like made out of plastic” and other nasty stuff. Um… How is it possible that supposedly smart people can in fact react with such ignorant comments? Let me tell you upfront that the dust clouds you see above not only exist and are up there, but their shape and position match exactly what you see in the image, at least to the point I was able to capture (not post-process) their signal. All that stuff was in my data, but the only way to make it surface was by using post-processing techniques that those who defend minimally processed images either don’t know or at best, don’t want to use (more often than not, they really don’t know – after all, why learn about something you’re not interested anyway?).

Is this all about beauty? If I cared about just beauty, why would I want “my” dust clouds to look like plastic? (that’s assuming that’s how they really look like)… Now I ask you… which photograph better documents what’s going on up there? Why should I limit the processing on this image, due to whatever some ethics dictate, and show a patch of the sky with nothing but stars and a few tiny galaxies, when I could greatly increase its value and show all what really is going on, even if that means pushing the data to its very limits? Maybe ethical in this case means we’d rather not see what’s behind all those stars? Well, I do.

Final words

Everything you’ve read so far is not meant to justify aesthetics, documentary driven astrophotography or advanced astroimage processing techniques. To me, they’re plentifully justified and need no exculpation. This article is simply an attempt to share my views on a much discussed topic, for which I think some people, for whatever reason, tend to disregard or downplay astroimages that include more than a simple non-linear stretch, while, in my very humble opinion, as stated, applying advanced post-processing techniques can be used to increase the documentary value of your data.

Last, let me add… While it’s true that some people resort to “easy Photoshop tricks” to post-process their astroimages, advanced image processing techniques aren’t what I’d call “easy” tasks, and calling tricks to anything that goes beyond a non-linear stretch often simply denotes either ignorance or arrogance – usually both. Advanced post-processing techniques require study, learning, experimentation, patience and sometimes frustration, unlike minimalist processing which often times doesn’t require any of that. You can choose to use them or not, but be respectful with your peers when you state your opinios, otherwise, the only one who may look clueless will be you – although of course, you will never ever think that’s the case (back to arrogance and ignorance).

Of course, learning and experimenting with new post-processing techniques and paradigms can too be challenging, rewarding and fun. And who is to tell others how they should have fun? Aren’t those some of the most valuable reasons for which we embarked in this journey after all?

Happy processing!